In the very late 15th century the church at Lakenheath received a new paint scheme. Very little of this scheme survives today. Before the new scheme was painted the older paintings, including the Passion cycle and St Edmund, were painted over with one or two coats of lime-wash. The new images were then painted on top of these thin layers of lime-wash. Unfortunately, when the wall paintings were uncovered in the late 19th century most of these thin layers of lime-wash were scrapped away from the walls, perhaps without even realising it, to reveal the paintings below. As a result, with only one notable exception, this 15th century scheme survives as only a few tiny fragments scattered across the surface of the earlier paintings.

These few fragments that do survive can actually tell us a good deal about the paint scheme in general - even if they can no longer show us the detail. It is clear that, of all the paint schemes found within the church, this scheme was one of the highest quality. The pigments that were used in the earlier schemes were almost all relatively cheap and easy to produce red and yellow ochre. Many of these may actually have even been produced locally. However, the new 15th century scheme contained expensive and hard to come by pigments such as Vermillion. These new pigments would have been far brighter than the earlier paints, making the images appear far more striking than the earlier schemes. Unfortunately, expensive though these pigments were, they have proved to be unstable over long periods of time. The bright reds of the Vermillion have now chemically changed on the wall and today appear as a very dark rusty brown.

NORTH ARCADE

Only a few very tint fragments of this scheme survive on the north arcade. However, even these faint and damaged fragments can possibly tell us a good deal about what they once looked like. On the central pillar, opposite the south door, St Edmund and the many figures of the Passion cycle were painted over. In this area, one of the most prominent in the church, a new figure became the focus of the congregations attention. Close examination of the few fragments that do survive show us a single eye painted on a deep red background - and a few other lines that appear to indicate reptile like scales. It would appear that, in common with a number of other churches at that time, the villagers commissioned an image of England’s newly emerging patron, St George, to decorate their church.

Left: The central pier of the north arcade. The red box shows the area where the few fragments of the 15th century scheme are located.

Above: Detail of the 15th century fragments. The red arrow indicates the possible dragons eye.

The late 15th century saw St George become a very popular subject for church wall paintings. As a soldier saint he had become popular with monarchs such as Henry V - and this popularity had been encouraged amongst all levels of society. Towns formed new Guilds of St George and local parish churches bought statues and banners to celebrate St George’s deeds. The most popular depiction of the saint, and most probably the subject of the Lakenheath painting, was St George slaying the dragon. The image to the right is also a very late 15th century depiction of the saint from Norwich. Although the Lakenheath image was unlikely to have been so fine quality its position, opposite you as you walked through the south door, would have been very striking indeed.

Roll over to enlarge

Roll over to enlarge

THE RISEN CHRIST

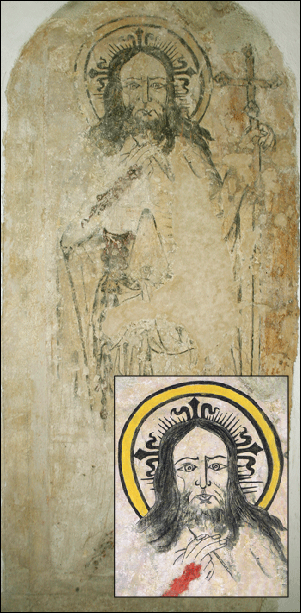

The only section of the 15th century scheme to survive intact is probably one of the most impressive of all the Lakenheath wall paintings that can be seen today. On the south side of the chancel arch, just above the doorway to the rood loft, is a full length painting of Christ. The image is of very high quality for a remote parish church and its style and technique were at the height of late 15th century fashion.

At the time the conservation project began this painting in particular was in a very poor state. At some point in the early 20th century the image had received a coat of wax. This was an accepted technique at the time and immediately made the images appear brighter. Unfortunately it had a number of long term problems that just weren’t realised at the time. The wax attracted dust and dirt - which made the painting dramatically fade over time. In addition, the wax sealed the surface of the painting, allowing mineral salts and moisture to build up in the plaster beneath. Eventually these salts would cause the plaster layers to separate from the wall. By the time the project began the whole central section of this painting was attached to the wall by only a few square inches of plaster. In another year or two it would have simply fallen off the wall.

The painting was created in the fashionable ‘grisaille’ style (so named after the French word ‘gris’ - or grey) that appeared at about this time. This style was very different from the almost garish bright displays of the earlier images. It involved painting the bulk of the image in an almost monochrome manner - much like the early woodcuts of the period. This flat image would then have been highlighted in certain areas, often with bright reds or golds, to draw attention to various parts of the image. This technique could be very effective and a superb example can still be seen today at Eton College Chapel - created to the very highest standards by painters who would also have been undertaking commissions for the Royal court.

Roll over to enlarge

BEFORE

AFTER

The Lakenheath image of the Risen Christ was created in exactly the same way as the magnificent images from Eton College. Although not of as fine a quality it was certainly far superior to anything that had yet appeared in the church. Like Eton, the Lakenheath image was also highlighted with red and gold. After cleaning the gold could still be very clearly seen in the halo around Christ’s head. The red, however, is far less obvious.

Close examination of the painting indicated that the bright red had originally been used to depict the blood on the wounds of Christ. Fir this an expensive Vermillion pigment had been used. Unfortunately, with the passing of the centuries, the bright Vermillion had gradually undergone a chemical change - leaving it a dark rusty brown colour. However, if you look very closely at these areas it is still possible to see a few specks of the bright red Vermillion - giving some idea of how striking this image would have originally looked.

Right: A detail from the superb late 15th century wall paintings from Eton College Chapel. Originally created in an almost monochrome ‘grisaille’ style, they were then highlighted with red and gold - as seen on the horse harness fittings.

Above Left: close up of the are of the red Vermillion on Christ’s hand. Only a few specks of bright red can now be seen.