A very good question with no really clear answer—although there are a number of theories. Many people believe that the Biblical stories shown in the wall paintings acted as ‘books for the illiterate’. Most of those people who attended church in the middle ages couldn’t read or write English—and they certainly couldn’t understand the language of the church services which were carried out in Latin. The images may have acted as visual reminders of the Bible stories.

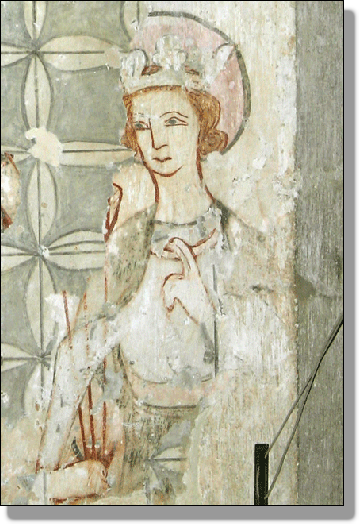

However, this obviously isn’t true of all medieval wall paintings. Some show images of Saints that are linked to the church or are of particular local importance (as with St Edmund at Lakenheath). Others are purely decorative and, as at least one of the schemes at Lakenheath shows, may have been paintings of things such as wall hangings or decorative stonework. These, it would appear, have no real religious connections and might have been painted simply to brighten up the inside of the church.

The earliest surviving church wall paintings so far located in England date back to the Anglo-Saxon period. Obviously very few of these early paintings survive today—so it is difficult to know if these paintings were as common then as they were several centuries later. Here at Lakenheath the earliest identified paintings have been dated to the early or mid 13th century (1200-1250). At this period such paintings were commonplace and could have been found in most churches in England. What is particularly unusual about the paintings at Lakenheath is that we have surviving fragments for five different painting schemes spanning a period of about four centuries.

The short answer is that we are really not sure. We know that they were probably commissioned and paid for by the parish. Occasionally a rich parishioner might have commissioned a particular wall painting themselves—or left money in their will for a painting to be created. We do know that many local people bequeathed money to the church here in Lakenheath. In 1454 John Horold, a local farmer, left money to pay for two new bells for the church tower—both of which still hang there to this day. A few decades later, in 1483, William Lacy left money that was to pay for seating in the church, a new pulpit and repairing the nave roof. However, no evidence has been found that mentions payments for painting the church.

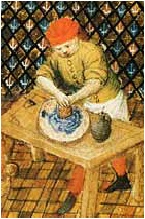

Even less is actually known about the craftsmen who carried out the work. The quality of the various paintings varies enormously and it is likely that at least some of the painters were local people. We do have evidence of one or two individuals who are recorded in royal or cathedral account books as being painters but it is highly unlikely any of these people worked here in Lakenheath. All that is known of them is the art that they left behind.

The paints were made up from two separate parts—a pigment, or colour, and a liquid binding ingredient. The binding ingredients were usually things such as water, egg paste, animal based glues and casein (curd from sour milk). More costly paints, unlikely to have been used here in Lakenheath, could be bound with linseed oil.

The actual colours were produced in many different ways and the pigments often came from some very unusual sources. The simplest colours were the blacks and whites, both used extensively in Lakenheath, which could be most simply produced from charcoal or slaked lime. Rich reds could be obtained from vermillion (in expensive cases) or red lead and red ochres. The ochres, naturally occurring iron-rich earths, could also be used to produce a variety of oranges and yellows. The more unusual colours, such as blue , were also the most expensive. The finest blue pigment, ultramarine, was made from crushed lapis lazuli—and was as expensive as gold.

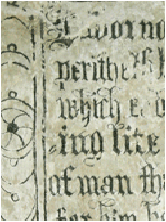

In the 16th century England went through a protestant revolution. The protestant reformers wished for a return to a more simple church; a church based upon the teachings of the Bible and the word of God. They believed that the Roman Catholic church was surrounded by superstitious rubbish that had nothing at all to do with God’s teachings. At first these reformers were in the minority. However, when King Henry VIII wanted a divorce from his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, he found that the Catholic church would not support him. In response Henry declared himself head of the church in England—a church with protestant leanings.

Over the following decades the reformers gained further influence until, under Henry’s son, Edward VI, they launched a full scale attack upon the ‘superstitions and idolatry’ of the medieval church. Images were banned, rood crosses were to be taken down, ornaments, vestments and high altars were outlawed. A particular target of the reformers were the paintings that covered the walls of so many English churches. These were to be whitewashed over and replaced with Biblical texts—as we can see today at Lakenheath. Ironically for the reformers, it was this protective layer of whitewash that has preserved many of these paintings for so long.

The truth is that we are not really sure. It may sound odd that the actual discovery of the paintings went without any real comment but, here in Lakenheath, this does appear to be the case. What we do know is that they were exposed and visible by October 1886 when the church was visited by the antiquarian C. E. Keyser. Keyser made note of a number of paintings, including some that appear to have been lost in the following century. In addition, a letter written to Central Council for the Care of Churches in 1912 mentions that ‘some mural paintings are still to be traced on the chancel arch’. As any visit to the church will make plain these paintings are also no longer visible.

As a result of this it is generally assumed that the paintings were first uncovered during a major restoration of the church that took place in 1864. However, we can never be entirely certain. It is also likely that certain badly damaged images were subsequently recovered with limewash in a further restoration of 1904.

The paintings have been exposed to the elements for over a century and, during that time, have received little in the way of conservation. It was common practise at the time they were rediscovered to apply coats of wax or varnish to newly uncovered paintings. Sadly, these early conservation attempts often did more harm than good. Luckily most of the Lakenheath paintings were not treated in this way. However, the paintings have suffered from a number of other things. At various times in the past leaks in the roof have allowed water to run across the surface of the paintings, leaving the pale streaks across the surface. This has also encouraged the layers of paint and plaster to ‘delaminate’ - to split apart from each other. If urgent work had not been carried out then, within a very few years, the paintings would have simply crumble away to dust.