King Henry VIII’s split away from the church of Rome marked the beginning of the Protestant reformation in England. To begin with Henry’s policies in relation to church services and decoration were relatively conservative - and he still proudly titled himself ‘fidei defensor’ (defender of the faith), a title actually given him by the Pope. Then, in 1536, Henry published the ‘ten articles’. These statements began to lay the foundations for a new protestant church.

Whilst the ‘ten articles’ did not ban the use of images within churches they did state that such images were only to be used as ‘remembrancers’ - and were not to be worshiped in their own right. However, for many of the more radical reformers these changes did not go far enough - whilst many traditional catholics felt they had gone too far already. When Henry died and his young son, Edward VI, came to the throne in 1547 the reformers found themselves in power. Under Edward the church was about to undergo one of the most dramatic changes in history.

Roll over to enlarge

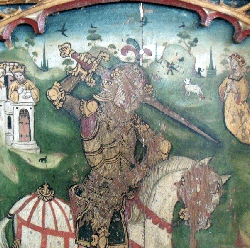

Above: Section of the rood screen from Wellingham, Norfolk. The 16th century reformers scratched out the face of St George - quite literally ‘defacing’ the image. Not satisfied with removing the saints face - they scratched out the head of the horse as well.

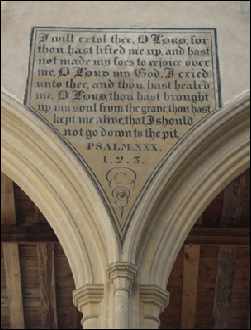

Below: At Wiveton on the Norfolk coast a whole series of text panels, very similar to that found at Lakenheath, still run down both sides of the nave.

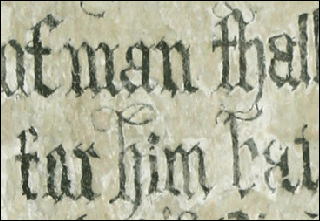

Below: the text panel after conservation. The inscription reads:

“Labor not for ye meate which

Perisheth but for the meate

Which endureth unto everlast-

Ing life, which the sonne

Of man shall give unto you

For him hath god the father

Sealed. I am ye breade of life

Which came downe

From heaven.

John.6.27”

Under Edward and the protestant reformers wall paintings and church images came under serious attack. Images were deemed ‘superstitious’ and ‘idolatrous’ and were ordered to be destroyed. In many cases reformers actually physically attacked churches - smashing the stained glass windows, statues and scrapping the paintings from the walls. Many images, some of the most lovely of medieval survivals, had their faces gouged from the walls - being literally ‘defaced’.

At Lakenheath the reformers did not attack the walls with such zeal. All the wall paintings, some of which had only been created a few decades earlier, were lime-washed over and hidden. Ironically, it was these layers of reformation lime-wash, that were supposed to destroy the images, that actually ensured their preservation until the present day. Sealed beneath the whitewash the images were safe from later puritan reformers who, had they known they were there, would undoubtedly have destroyed them.

Many people think that the protestant reformation marked the end of wall paintings in English parish churches. It didn’t. Edward VI’s injunctions against images may have done away with the saints and angels of the medieval paintings - but it also stipulated that new paintings should take their place. These new images, like the new protestant church from which the grew, were to return to an emphasis upon the holy texts and scriptures. Where St George and a dragon had once battled their way across church walls, dour texts and commandments took their place.

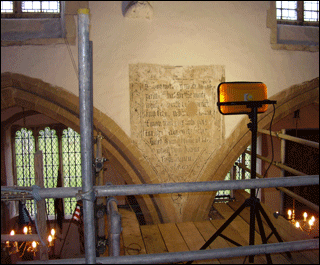

At Lakenheath these new images took the form of large blocks of text painted in decorated borders in the spandrels of the arches. Today only one complete text survives - along with the upper section of the frame of one other. Located high on the south arcade the text is from John, chapter six. Although only one complete text frame now survives it is likely that they extended down both sides of the nave - much like the examples that can still be seen today at Wiveton on the north Norfolk coast.

The examples at Lakenheath was probably first painted in the early 17th century and may have replaced earlier text frames. It was probably clearly visible for well over a century and examination of the surface showed that it had been repainted at least four or five times. During the conservation project much of the over-painting was removed to reveal the original text and making it readable once again.

It is likely that the text frames at Lakenheath were still visible until well into the 18th century - before they too were lime-washed over. However, only a century later they, along with all their glorious medieval predecessors, were ‘rediscovered’.